Although relatively rare, motor neurone disease (MMN) in horses is a serious neurodegenerative disorder that affects the lower motor neurons responsible for controlling skeletal muscles. The condition, which is comparable to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in humans, leads to progressive muscle weakness, atrophy and eventual paralysis. Early diagnosis of SMA is crucial to improving the quality of life of affected horses and implementing appropriate management strategies.

What causes this disease?

Equine Motor Neurone Disease (EMND ) is a degenerative condition whose precise aetiology remains unknown. It is characterised by degeneration of somatic motor neurons in the ventral horns of the spinal cord and certain cerebral nuclei. Affected horses suffer from neurogenic atrophy of the skeletal muscles, mainly type I muscle fibres.

First discovered in 1990, MMN affects adult horses aged between 2 and 25 years of both sexes. Clinical signs result from degeneration of motor neurons located in the cervicothoracic and lumbosacral parts of the spinal cord. Affected neurons often show abnormal nuclei and punctiform eosinophilic inclusions.

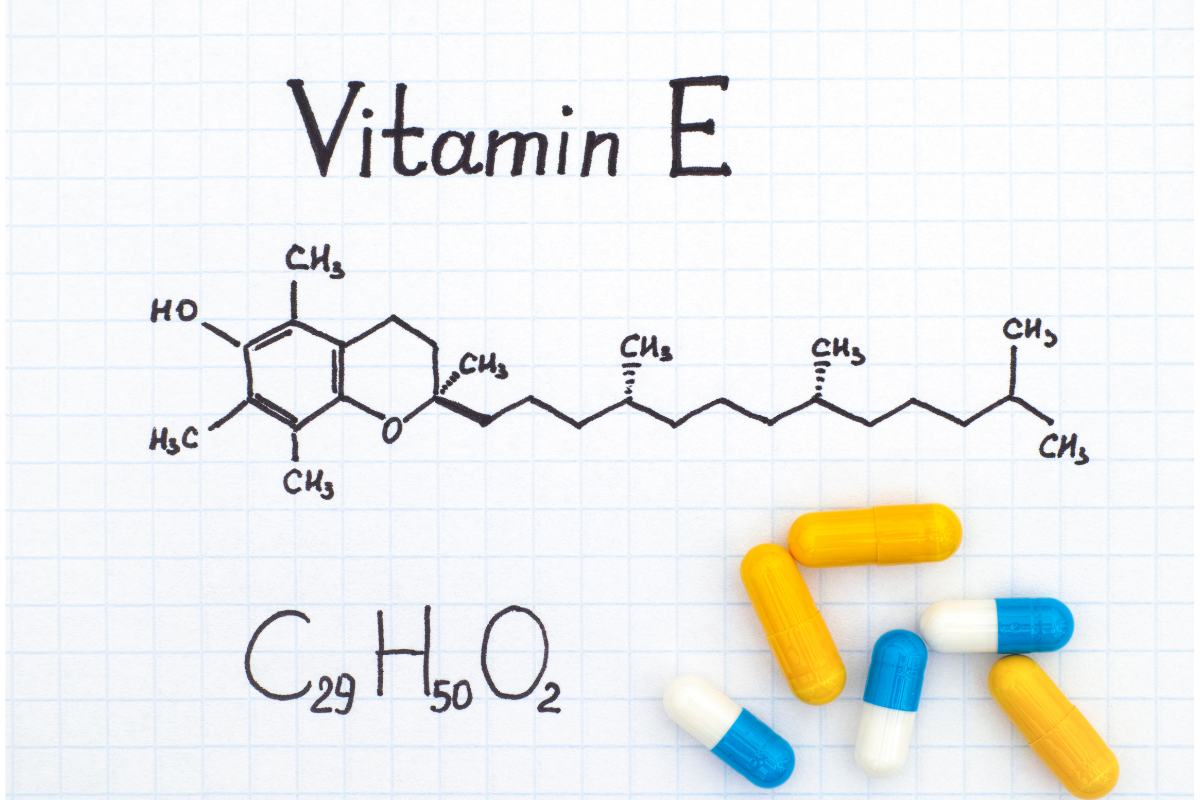

The commonly accepted hypothesis is oxidative stress causing degeneration of motor neurons, particularly those with high oxidative activity (alpha motor neurons). A deficiency in antioxidants, particularly vitamin E, is a major risk factor. A Cornell University study showed that horses fed a diet low in vitamin E for a long period developed symptoms of SMA.

Additional risk factors include pasture quality, bioavailability of vitamin E sources and intestinal absorption capacity. Affected horses also had elevated levels of copper and iron, suggesting a possible contribution of these minerals to the development of the disease.

What are the symptoms of motor neurone disease in horses?

The symptoms of motor neurone disease in horses can vary depending on the severity and duration of the disease. They often appear in acute or chronic form.

Acute form

In the acute form, horses show rapid trembling, particular postures with limbs bunched under the body, and spend more time recumbent. Other symptoms include a low head carriage, sweating, elevated tail carriage and muscle fasciculations. Despite these symptoms, appetite remains excellent and intestinal transit normal.

Clinical examination often reveals symmetrical amyotrophy of the muscles of the shoulder, neck, back and sacrum. Retinal abnormalities, with pigment deposits, are also common. The acute phase generally lasts from 2 to 8 weeks. Horses may recover some of their muscle mass, but rarely enough to be remounted. A resurgence of symptoms may occur several years later, often leading to euthanasia.

Chronic form

After the acute phase, the horse’s condition may stabilise or progress more slowly. Symptoms include weight loss despite a good appetite, generalised amyotrophy, weakness and prolonged periods of recumbency. Horses adopt relieving postures and may show a temporary improvement in muscle mass.

The disease mainly affects horses that have no access to grass and are fed a diet rich in concentrates and poor-quality hay. In 80% of cases, a transient stabilisation is observed, followed by a progressive recurrence of symptoms, leading to euthanasia. In 20% of cases, the disease progresses rapidly as soon as the first symptoms appear.

How is the disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis of motor neurone disease in horses is based on a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests and tissue biopsies.

Routine haematology and biochemistry tests reveal few abnormalities. There was, however, a slight increase in muscle enzymes (CK, AST) during the active phase of the disease. A drop in the plasma concentration of α-tocopherol (vitamin E) is often observed in 90% of cases. Glucose absorption tests are abnormal in around 30% of horses.

Diagnosis is easier in horses with an active form of the disease. The sudden onset of weakness, associated with tremors without ataxia or depression, is suggestive of SMI. Veterinarians use muscle biopsies of the sacrocaudalis dorsalis medialis muscle and the ventral branch of the accessory nerve to confirm the diagnosis.

Blood tests are essential to determine vitamin E levels, which are generally very low in horses with MMN. Abnormal glucose uptake and elevated muscle enzymes are also indicators.

Muscle and nerve biopsy revealed degeneration of the lower motor neurons. Post-mortem findings show accumulations of lipid pigments in the capillaries of the spinal cord. Microscopic lesions were also found in certain cranial nerves.

What treatments are available?

Unfortunately, no study has proved the effectiveness of a curative treatment for motor neurone disease in horses. However, certain measures can help to stabilise and improve the horse’s condition.

Veterinarians recommend supplementing horses with low plasma or tissue concentrations of vitamin E. Recommended doses vary from 5,000 to 8,000 IU per day. They should preferably be administered without selenium to avoid poisoning. Feed should include fresh forage, as vitamin E is more bioavailable in this form.

An anti-oxidant treatment, often based on corticosteroids such as prednisolone, is introduced. The aim of this treatment is to stabilise the horse for as long as possible. However, it generally does not allow the horse to resume physical activity. Weight regain and stabilisation of the clinical condition are possible, but recurrence is frequent.

Initial infusions and corticosteroid therapy in decreasing doses may be administered to combat oxidative stress. Euthanasia is often the final outcome, despite temporary clinical improvements.

What are the natural alternatives?

In addition to conventional medical treatments, certain natural alternatives can be considered to help manage motor neurone disease in horses.

A diet rich in natural antioxidants, such as vitamin E, is crucial. Horses should have access to green pasture, which is a natural source of vitamin E. If this is not possible, supplementation with natural vitamin E(d-alpha-tocopherol) is recommended.

Certain medicinal plants, such as milk thistle, can have beneficial effects thanks to their antioxidant properties. Milk thistle contains silymarin, which is known to protect cells against oxidative damage.

Natural supplements, such as fish oils rich in omega-3, can also help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. Fish oils contain essential fatty acids that support cellular health.

Ensuring a clean, stress-free environment can also play a role in managing SMA. Regular access to pasture and a balanced diet help to reduce the risk of vitamin E deficiency.

What are the means of prevention?

Prevention of motor neurone disease in horses relies mainly on proper nutrition and careful management of the horses.

To prevent SVD, it is crucial to ensure that horses receive a sufficient amount of vitamin E in their diet. A vitamin E supplement may be necessary for horses fed only hay.

Access to green pasture is a natural and effective source of vitamin E. Horses that graze regularly are less likely to develop a deficiency.

Natural forms of vitamin E, such as d-alpha-tocopherol, are more efficiently absorbed by the body than synthetic forms. Consult an equine nutritionist to determine the specific needs of each horse.

It is important to remain vigilant for the early signs of SMI. A veterinarian should be consulted as soon as neurodegenerative symptoms appear. Regular monitoring and feed analysis can help prevent the disease.