Anthrax is a serious bacterial infection caused by Bacillus anthracis. This pathogen affects both humans and animals. In the past, it has caused devastating epidemics among animal industry workers, farmers and soldiers. Despite its rarity in developed countries thanks to prevention and control measures, anthrax is still a public health issue in many regions, particularly where health and economic conditions are precarious.

What is the pathogen?

Anthrax is a zoonosis caused by Bacillus anthracis. This infection can affect all species of mammal, domestic or wild, mainly herbivores, as well as some species of bird.

Bacillus anthracis is a gram-positive, non-motile, spore-forming bacterium. Its spores are highly resistant. They remain viable in the soil for decades, resisting drought, heat and exposure to various disinfecting agents. In environments rich in amino acids and glucose, such as blood or tissues, these spores transform into vegetative forms in both humans and animals.

The antiphagocytic capsule and toxins of Bacillus anthracis determine its virulence. These toxins are made up of the protective antigen, the oedematous factor and the lethal factor. They play a crucial role in the pathogenic manifestations of the disease. They cause extensive local oedema and massive release of cytokines by macrophages, which can be fatal in severe cases.

Anthrax manifests itself differently depending on the route of infection. Ingested or inhaled spores germinate in the body, multiply and can cause severe or even fatal symptoms. Skin infections can occur following contact with spores, often in people working in close contact with infected animals or their products.

Understanding the pathogenic mechanisms of anthrax is essential for preventing and controlling this dangerous disease. By studying its virulence factors and transmission routes, we can develop more effective prevention strategies to protect public and animal health.

Anthrax, a bacteriological weapon

Biological weapons are a category of weapons that use organisms, such as pathogenic germs, to weaken enemy armies or populations by spreading potentially fatal or simply incapacitating diseases. Because of their damaging potential, these weapons have been classified as weapons of mass destruction. Bioterrorism involves the dispersal of germs capable of triggering fatal diseases.

The use of biological weapons dates back to the twentieth century, particularly during the Second World War. In the 1930s, as part of a research programme, the Japanese army used biological weapons in its conflict with China. Tests involving anthrax were carried out, as were inoculations of thousands of prisoners with pathogens such as plague.

Research into biological weapons intensified during the Cold War, mainly in the USA and the USSR. The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union led to the emergence of modern bioterrorism. In the 1990s, the Aum sect in Japan carried out several attempted attacks using biological weapons. These included attempts to use the Ebola virus and anthrax, both of which failed. In 1995, the sect chose sarin gas, a simpler and safer chemical weapon, for the attack on the Tokyo metro.

Later, in 2001, a series of anthrax attacks took place in the United States, constituting the first true bioterrorist attacks. Envelopes contaminated with anthrax were sent out, causing 22 cases of infection, five of them fatal. These attacks highlighted the threat posed by biological weapons and prompted major investigations to identify those responsible.

What does the disease look like in animals?

The species susceptible to anthrax infection include all mammalian species, both domestic and wild, with an emphasis on herbivores, as well as a small number of birds. Symptoms of infection vary between animal species and generally manifest themselves in three distinct forms.

The first form causes an acute digestive infection. Symptoms include abdominal pain, cessation of rumination, neck oedema and excrement containing black blood. The second form triggers a respiratory infection. It manifests itself as a dry cough, acute oedema of the lungs, frothy rust-coloured nasal excretions and oedema of the neck. The third form initiates a generalised infection, or septicaemia. This may appear immediately or may follow on from the earlier forms, causing the sudden death of the animal.

Anthrax affects both farmed and wild animals. Among domestic animals, cattle and sheep are more susceptible than horses and goats. Symptoms of the disease in animals can be acute, sub-acute or chronic. In severe cases, the animal may succumb within two to three days, developing a haemorrhagic syndrome characterised by bleeding from the nose, mouth and anus.

Historical descriptions of the disease show specific manifestations. For example, in sheep, the disease appears rapidly and causes sudden death within a few hours, or progresses slowly with a gradual worsening of symptoms. In horses, it manifests itself either as a rapid onset of anthrax or as a slow-blooded disease. Cattle develop similar symptoms with distinct signs such as angina accompanied by a ganglion mass between the jaws. Carnivores, birds and cold-blooded animals are generally less susceptible to the disease, except under certain specific conditions. On the other hand, wild animals, primates and deer are the most susceptible.

How is the disease transmitted?

Transmission of anthrax in animals can occur via the digestive tract or by inhalation, mainly in the following circumstances:

- Grazing on spore-contaminated land, often referred to as “cursed fields”.

- Ingestion of spore-contaminated water, hay, straw, silage or other feed.

When animals graze on contaminated grass, particularly near charcoal corpses, or eat fodder from contaminated areas, they expose themselves to mucosal lesions. These lesions encourage the transmission of disease. The bacterium’s spores remain in the soil for many years. Activities such as earthworks or heavy rain in the hot season can bring them back to the surface. In this way, they contaminate the environment.

Transmission to humans occurs mainly through skin contact with infected animals, their carcasses or by-products such as offal, hides, skins, wool and horns. Ingestion of contaminated meat or milk is an exceptional route of transmission in France. In addition, inhalation of spores, particularly when handling contaminated wool, can lead to a specific disease in workers, known as “wool carder’s disease”.

Infection in humans can also occur through skin contact, ingestion, inhalation or injection. Open wounds increase susceptibility to skin infection, which can also develop on intact skin. Skin infection is not generally contagious, but human-to-human transmission has been reported in very rare cases. Ingestion of undercooked meat or milk containing vegetative forms of the micro-organism can lead to gastrointestinal infection, while inhalation of spores can cause an often fatal pulmonary infection. This disease can also be contracted intentionally (bioterrorism).

What are the symptoms in humans?

The various forms of contamination by Bacillus anthracis have different effects on the body. In humans, there are three forms of contamination: cutaneous, digestive and respiratory. A fourth form of contamination is possible in drug addicts, through injection with a contaminated syringe. Most anthrax patients develop the disease between one and six days after exposure. However, the incubation period for inhalation anthrax can exceed six weeks.

In humans, the external cutaneous form is the most common and often progresses favourably. However, without treatment, this form can lead to death in 5-20% of patients. Internal forms, such as visceral, gastrointestinal or respiratory, depend on the route of entry of the bacteria and can cause fatal septicaemia without treatment. The respiratory form is the most severe and the prognosis is generally unfavourable, especially without rapid administration of a massive parenteral antibiotic treatment.

Cutaneous form

The cutaneous form of anthrax begins as a dark red, painless, itchy papule, appearing 1 to 10 days after exposure to infectious spores. This papule then develops into a vesicle surrounded by an area of erythema and severe oedema. Ulcerations and indurations form, followed by the appearance of a black eschar, known as a malignant pustule. Local adenopathy may occur, accompanied by malaise, myalgia, headache, fever, nausea and vomiting. It may take several weeks for the wound to heal and the oedema to disappear.

Cutaneous anthrax is the most common form (95% of cases). The infection may be accompanied by lymphangitis, painful adenopathies and severe oedema, with the possibility of bacteremia. Appropriate oral antibiotic treatment is effective, but in the absence of treatment, the mortality rate can be as high as 20% in cases of sepsis.

The heroin addict form occurs following injections of heroin contaminated with anthrax spores. It is characterised by infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues at the injection site, with possible dermohypodermatitis, necrosis, fasciitis and bacteraemia. The development of a typical bedsore is rare, and the prognosis in these cases is severe.

Gastrointestinal form

The digestive form of anthrax is characterised by a rapid onset, marked by high fever, headaches, abdominal pain and the presence of black blood in the stools. If not treated quickly, this form of the disease can be fatal. It results from the ingestion of meat containing endospores, but remains uncommon. Gastrointestinal anthrax occurs when spores are found in the gastrointestinal tract, causing two types of symptoms: an oropharyngeal form, with oesophageal or oral ulcers and septicaemia; and an intestinal form, characterised by nausea, vomiting, bloody diarrhoea, intestinal perforation and septicaemia, possibly accompanied by ascites.

This form can be treated, but mortality varies between 25% and 60% depending on the speed of treatment. Symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and haemorrhagic diarrhoea, with the possibility of intestinal necrosis and fatal septicaemia. Gastrointestinal anthrax is highly lethal, while oropharyngeal anthrax manifests itself as ulcerated, oedematous lesions in the throat, accompanied by swelling of the cervical lymph nodes and symptoms such as sore throat, fever and difficulty swallowing.

Respiratory form

The respiratory form of anthrax is characterised by a rapid onset, beginning with a common cold and rapidly progressing to severe and often fatal lung disease. It results from the inhalation of spores via contaminated particles, generally in aerosol form. Inhaled spores are phagocytised by macrophages in the pulmonary alveoli, multiply and release toxins up to two months later.

Initial symptoms include fever, muscle aches, headache and dry cough, but no nasal symptoms. A few days later, there is a sudden deterioration with respiratory failure, chest pain and low blood pressure. Complications such as haemorrhagic meningitis or septicaemia occur in almost half of cases.

Although pulmonary anthrax accounts for less than 5% of cases, its mortality rate is extremely high in the absence of treatment, especially in exposed professions such as wool sorters. However, early treatment with modern antibiotic therapy can reduce mortality to less than 50%. This form is not contagious between humans.

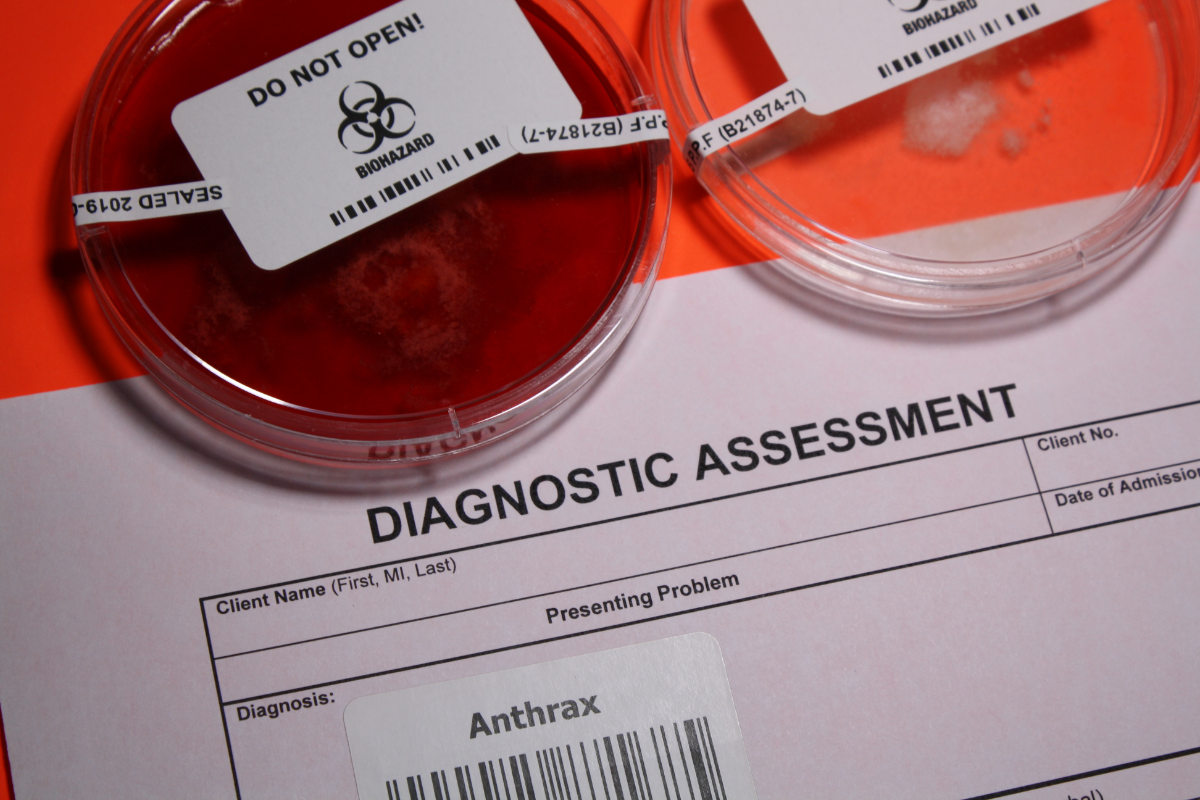

How is the disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis of anthrax involves several methods for identifying the germ at different levels. Culture of samples is common, although this method is time-consuming, while serology only becomes positive at a later stage. PCR diagnosis is also an option.

A history of occupational activities and exposure history is of paramount importance. Cultures and Gram stains of samples from various clinically identified sites, such as skin lesions, blood, pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid or faeces, should be performed.

It is essential to avoid certain pitfalls, such as using sputum examination and Gram staining to identify anthrax inhalation, given the rarity of the disease in the respiratory tract.

For microbiological diagnosis, professionals can use a variety of methods, including culturing samples on different types of biological fluids, direct examination of samples, specific PCR and serological tests (ELISA). An antibiotic susceptibility test is also recommended to guide antibiotic treatment.

If anthrax is clinically suspected, a level L3 laboratory should handle the samples. Reference laboratories can perform culture, antibiotic susceptibility testing and PCR. Any suspicion of anthrax should be discussed with the National Anthrax Reference Centre.

In terms of sample management and transport, triple packaging is recommended to ensure the safety of samples. Isolation of untreated infected patients is also important to avoid potential human-to-human transmission.

How can anthrax be prevented?

Anthrax is highly contagious, requiring only standard hygiene precautions. The most commonly used vaccine, the Sterne strain, is live and reserved for veterinary use because of its potentially dangerous inflammatory reactivity in humans. For humans, acellular vaccines containing the PA protein from Bacillus anthracis are used in the UK and US.

To prevent the risks associated with anthrax, it is necessary to vaccinate livestock in at-risk areas. Livestock premises and equipment must also be cleaned and disinfected. Workers must receive specific training on anthrax risks and prevention practices.

In the event of infection, the authorities apply the control measures defined in the Rural Code. These include continuous surveillance of livestock, isolation of infected animals, disinfection of premises and a ban on selling products from affected farms.

It is crucial to reduce potential sources of contamination, in particular by avoiding contact with animal faeces and by handling corpses or animal waste with waterproof gloves.

As far as vaccination in humans is concerned, no effective and safe vaccine is currently available in France. However, high-risk individuals use a vaccine containing a protective antigenic protein, requiring a series of intramuscular doses to ensure effective protection.

In the event of exposure to anthrax spores, it is recommended that a series of vaccines be administered along with preventive antibiotic therapy. In an emergency, the vaccine should be administered even after exposure, unless there has been a previous severe allergy.

To prevent contamination of pastures and livestock farms, it is essential to incinerate the corpses of anthrax-infected animals. In the event of an epidemic, antibiotics are effective in the early stages of the disease. Vaccination of non-diseased animals is recommended.

What is the treatment?

Mortality associated with untreated anthrax varies according to the type and route of infection:

- Inhalation and meningeal anthrax: 100%

- Cutaneous anthrax: 10 to 20%

- Gastrointestinal anthrax: approximately 40%

- Oropharyngeal anthrax: 12 to 50%

Rapid management including accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment and intensive care can reduce mortality, particularly in cases of inhalation anthrax. Treatment includes administration of antibiotics and other drugs, and drainage of pleural fluid if necessary.

In cases of cutaneous anthrax without major complications, doctors prescribe various oral antibiotics for 7 to 10 days. These include ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, doxycycline and amoxicillin.

To treat severe forms of anthrax, such as inhalation anthrax, healthcare professionals administer a combined intravenous treatment. This treatment includes at least two antibiotics with bactericidal activity and a protein synthesis inhibitor. They administer these antibiotics for at least two weeks. Oral treatment follows for 60 days to prevent relapses.

Post-exposure prophylaxis involves the administration of antibiotics and possibly vaccination in subjects exposed to inhalation anthrax. In the event of drug resistance, doctors may consider therapeutic alternatives, such as using specific antibiotics or monoclonal antibodies. Drainage of pleural fluid is recommended in cases of respiratory failure to ensure adequate ventilation.

Finally, it is essential to follow the recommendations of public health authorities, such as the CDC, regarding anthrax management and prophylaxis in order to optimise the chances of recovery and reduce the spread of the disease.

How is anthrax spread around the world?

In the 20th century, epizootics were frequent in Europe and Asia, and rarer in Australia and Canada. They occur more often in the warmer months, when drought and heavy rain alternate. Permanent endemic foci have been identified in Ethiopia, Iran, China and Mexico. In Europe, the disease is particularly prevalent in the Mediterranean region.

In France, there are regular outbreaks of the disease in cattle. Every year, cases occur in certain departments of the Massif-Central, Savoie and the North-East. Between 1999 and 2009, the authorities recorded 74 outbreaks of anthrax. They reported cases in July 2009 near La Rochette in Savoie, in July 2012 in Rhône-Alpes and in August 2016 in Moselle.

Between 2002 and 2010, doctors diagnosed four cases of human infection in France. These cases mainly involved cutaneous anthrax. The patients had handled contaminated sheep’s wool or touched infected cow carcasses.

In the Far North of Siberia, global warming represents a major risk. Melting permafrost can release the bacteria, which remain infectious for thousands of years. In the summer of 2016, after 75 years in the deep freeze, Bacillus anthracis reappeared in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District of Russia’s Far North, probably carried by a thawed reindeer carcass brought to the surface.

An epidemic mainly infected reindeer, affecting more than 80% of the animal population. These sick animals showed skin symptoms that could be treated with antibiotics. However, almost 20% of cases developed fatal lung problems if they did not receive immediate treatment. The authorities quarantined the region and launched operations to incinerate the corpses using military helicopters and drones. They also recorded human casualties, including the death of a 12-year-old child and the slaughter of more than 2,000 reindeer.

Bacillus anthracis is classified as a potential bioterrorism agent. Historical incidents include the Sverdlosk epidemic in 1979 and the 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States.

What is the status of the disease?

From a public health perspective, anthrax is a notifiable disease in humans. In addition, the agricultural and general social security schemes recognise the disease as work-related and eligible for compensation. The French Labour Code classifies the bacterium responsible, Bacillus anthracis, in hazard group 3, and the WHO and OIE monitor it internationally.

In France, anthrax has been a notifiable disease since 2002. Local health authorities assess the risks and provide post-exposure treatment for those exposed, mainly livestock farmers, vets and rendering plant workers. The bacterium produces potentially fatal toxins. It is also considered a potential agent of bioterrorism due to its ability to form spores.

The Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail (Anses) has confirmed the suspected cases of anthrax. It is investigating to identify the origin of the bacterial strains. It is deploying public health measures to detect human B. anthracis infections rapidly, assess the risks of infected animals and inform health professionals and the public.

Initiatives to protect the health of animals and humans are being put in place. These initiatives include vaccinating livestock, strengthening meat inspection, monitoring human cases and raising public awareness.

Strict protocols guarantee disinfection and decontamination. Efforts are being made to secure the supply of essential medical supplies. In addition, risk communication and community mobilisation activities are being carried out to raise awareness and inform the public.

History of the disease

Anthrax has probably existed since ancient times, often confused with other ailments affecting livestock. Aristotle sometimes attributed the sudden deaths of grazing animals to the “venomous bite” of shrews. These deaths could, in fact, be the result of acute anthrax.

In the nineteenth century, medical historians linked this condition to mythological stories. They mentioned the tunic of Nessus and the plagues of Egypt in the Bible. Hippocrates used the term “anthrax” to describe a skin lesion reminiscent of anthrax. However, the exact nature of this lesion remains uncertain by modern standards.

The disease was officially recognised in the 16th century, notably by the Republic of Venice. Descriptions became more precise in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly among wool workers and wigmakers working with imported animal products.

In 1769, Fournier of the Dijon Academy identified the human disease in a more modern way under the name of “malignant anthrax”. He described various skin lesions and recognised that the disease was transmitted to humans by handling sheep’s wool.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, doctors and veterinary surgeons conducted intensive research into anthrax, because of its major health and economic impact. In 1876, Robert Koch demonstrated the ability of the anthrax bacterium to form spores.

Veterinary vaccines, initiated by Chauveau, Toussaint and Pasteur in the 1880s, considerably reduced animal mortality due to anthrax. However, these early vaccines had limitations in terms of duration of protection and stability. This led to subsequent research to improve their effectiveness.

Human anthrax vaccines got off to a rocky start in the 1910s . However, significant progress was made in the following decades, with the development of live vaccines in the Soviet Union and China, and inactivated vaccines in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1950s and 1960s.