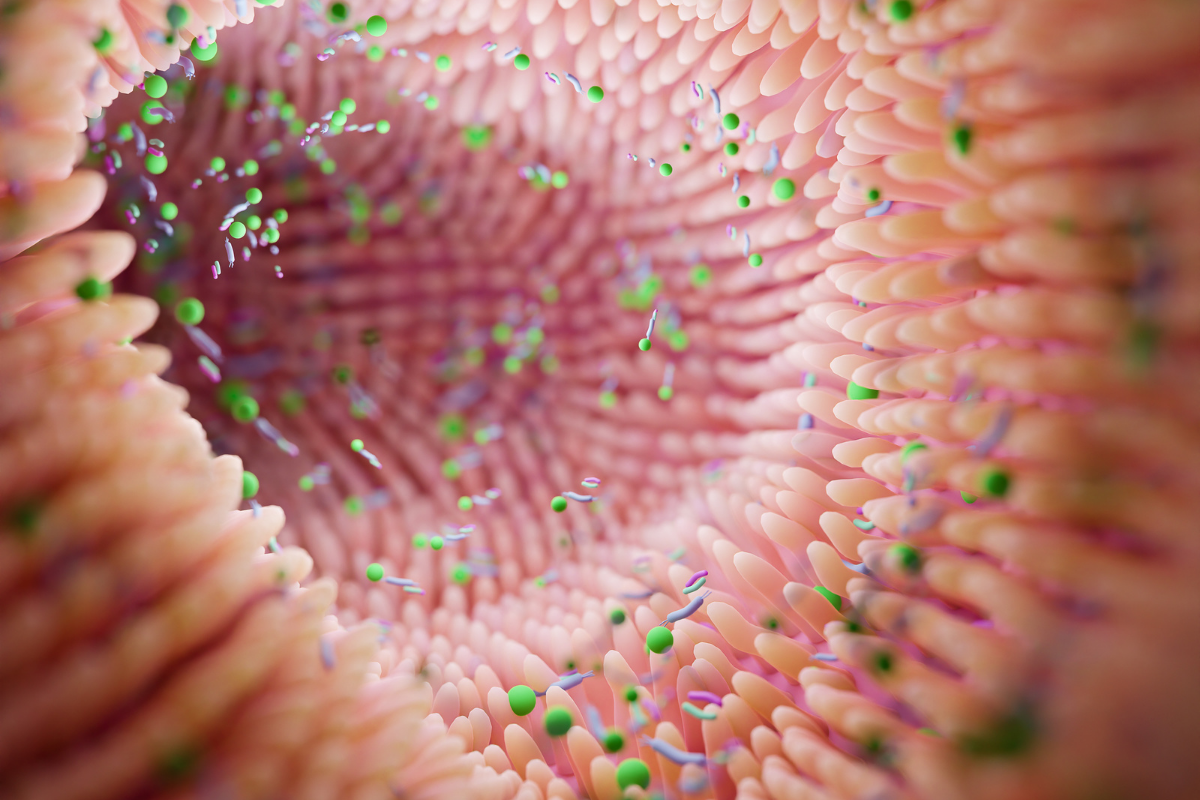

Dietary fiber, mainly of plant origin, resists digestion and absorption in the human small intestine. Unlike other nutrients, it passes intact into the colon. It is at this stage that the intestinal microbiota, a dense community of microorganisms in the large intestine, comes into play.

This microbiota ferments dietary fiber, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate and butyrate, each with specific health benefits. Butyrate, for example, is essential for colon health. SCFAs include anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, and recent studies also suggest their influence on mental health via the gut-brain axis. These SCFAs therefore play a crucial role in various physiological processes, contributing to digestive and general health.

What role does the colonic microbiota play?

The colon, or large intestine, is the terminal part of our digestive tract, dedicated primarily to the absorption of water and the breakdown of undigested food compounds absorbed upstream in the stomach and small intestine. This digestive compartment is very dense in micro-organisms that metabolise food residues, producing SCFAs that regulate the intestinal environment.

In addition to SCFAs, the colonic microbiota is also responsible for the production of certain essential vitamins, such as K and B vitamins. The diversity of this microbial community is crucial to overall health, influencing the risk of metabolic and autoimmune diseases.

One of the main functions of the colonic microbial community is to break down and ferment dietary fibre.

What are the natural sources of dietary fiber?

Cereal foods are a major source of energy and dietary fibre in the Western diet. Although whole grain products offer significant nutritional benefits, their acceptance is still limited. This low acceptance can be attributed to organoleptic changes (taste, texture) that can occur when fibre content is increased. However, whole grains are essential for a balanced, nutrient-rich diet, and they help to reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. In addition to whole grains, legumes, nuts and certain seeds are also excellent sources of dietary fibre.

Cereal foods and nutritional issues :

Cereal foods are widely consumed in various forms throughout the world, although they no longer form the base of the food pyramid in Western countries. Because of their honeycomb structure, the matrix of cereal foods (bread, biscuits, cakes, etc.) can be thought of as a solid foam, since their density is much lower than that of their components.

Because of their starch and protein content, cereal foods are the most important source of energy in our diet, and their protein fraction provides a wide range of amino acids. These foods are already the main source of dietary fibre in the Western diet, although whole grain products are not yet widely accepted or consumed, despite their high dietary fibre and micronutrient content.

So why talk about dietary fiberin fruit?

Some fruits, especially tropical ones, are rich in cellulose, gum, polysaccharide and sometimes lignin. Everyone knows that fruit, especially under-ripe fruit that is less rich in easily digestible carbohydrates, is an excellent laxative because it provides water, allows the bolus to retain water and facilitates transit.

What are the pharmacological properties of fiber?

Dietary fiberhas a number of health benefits. Firstly, it promotes water retention, increasing the viscosity and volume of faecal matter, which facilitates transit.

Secondly, the microbial fermentation of fibre produces SCFAs, which help to retain water and increase stool hydration. SCFAs have notable anti-inflammatory effects, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting the production of regulatory T cells, which are essential for controlling immune responses. Certain fibers, such as gums and mucilages, can adsorb bile salts in the colon, increasing liver synthesis and reducing blood levels of triglycerides and cholesterol.fibersCalorie intake is very low, as these fibersare not digested to any great extent by microbes in the colon. On the other hand, it adsorbs and eliminates fats, proteins and certain cations. In fact, some people have seen this as a way of preventing atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease, given our high-calorie, high-fat diet.

But before proposing a diet using these dietary fibers, wouldn’t it be wiser to simply reduce our intake of sugars and fats?

Finally, the biggest advantage demonstrated is the increased volume and hydration of the alimentary bolus. In short, a laxative effect that allows the bolus to be evacuated, thereby preventing diverticular disease of the colon, which often leads to cancer within a few years. This phenomenon has been observed in various countries where the diet is too rich but low in fiber.

To reap the many benefits of dietary fiber, we recommend increasing your intake to around 30 grams a day by including more fiber-rich vegetables, fruit and cereals in your diet. However, it is important not to consume too much fiber, as this can reduce the absorption of essential minerals such as iron and calcium. A balanced approach is therefore essential to optimise digestive and general health, taking care to diversify sources of fiberto avoid deficiencies.

Sources

- Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review

- Dietary fiberintake and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies

- The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease and Its Implications for Translational Research