Rapamycin is known for its immunosuppressive effects, but it could also act as an immune modulator. This dual capacity opens up new prospects for its use in rejuvenating the immune system. By inhibiting the mTOR pathway, rapamycin influences several ageing processes, offering significant potential in the treatment of age-related diseases.

Rapamycin and its derivatives: a brief history

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, was first introduced in the 1990s for its immunosuppressive properties. Its use was quickly adopted in organ transplantation. However, because of its patent, its commercial potential was limited, which dampened interest in in-depth research. Rapalogues, derivatives of rapamycin, were developed to extend its application.

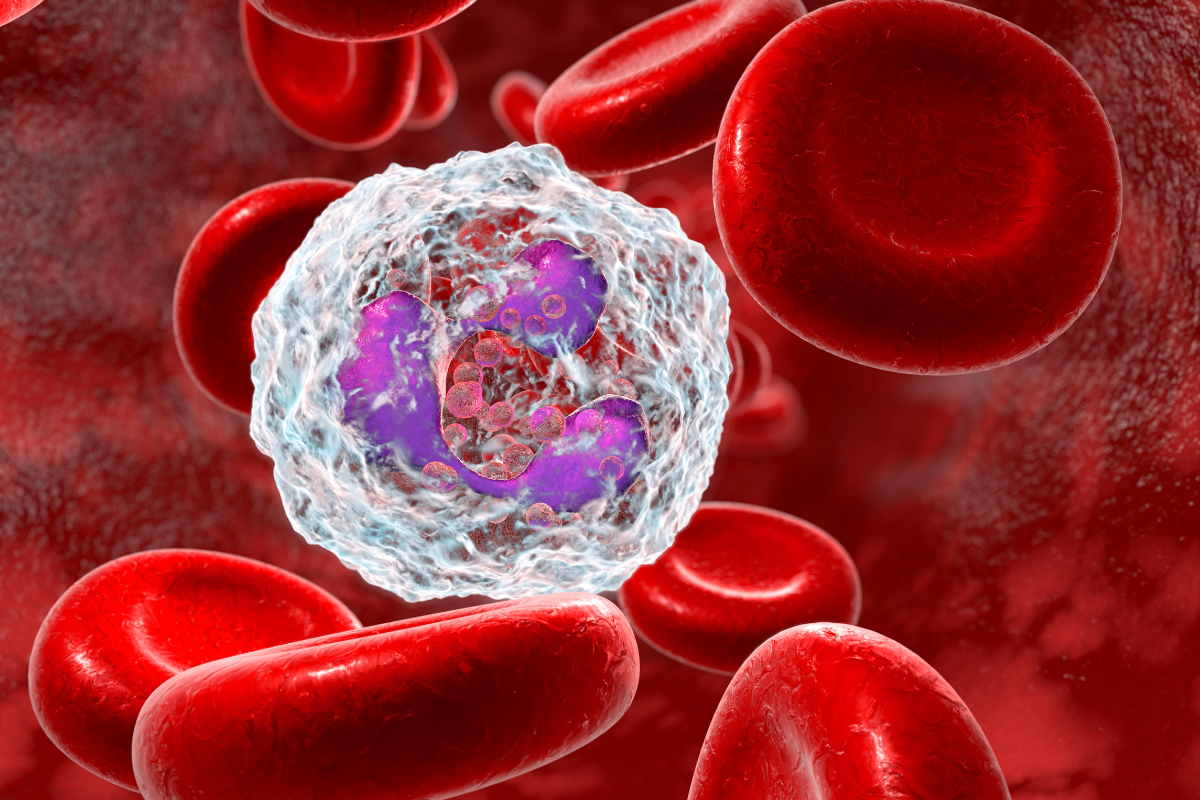

Rapamycin binds to the FKBP12 protein, forming a complex that inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), specifically the mTORC1 complex. This inhibition reduces protein synthesis and alters various cellular processes, including autophagy, a cellular degradation pathway essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Rapamycin and immune rejuvenation: What the science says

In 2009, a pioneering study showed that rapamycin could rejuvenate the immune systems of aged mice. Mice treated with rapamycin for six weeks before receiving a flu vaccine showed protection comparable to that of young mice, suggesting a restoration of immune function. Studies on other animal species, such as yeast, worms, flies and fish, have also shown that reducing mTOR signalling can extend lifespan by up to 60%.

More specifically, untreated aged mice showed reduced protection after vaccination, with only 30% survival following exposure to a lethal dose of influenza virus. In contrast, mice treated with rapamycin had a 100% survival rate, similar to that of young vaccinated mice. This demonstrates that rapamycin can improve the immune response of aged mice, potentially by restoring essential cellular functions altered by ageing.

A study by Joan Mannick and colleagues showed similar results in humans. Elderly people giveneverolimus, a rapamycin derivative, showed an improved response to influenza vaccination. Other human studies have shown that rapamycin and its derivatives improve physiological parameters associated with ageing in the immune, cardiovascular and integumentary systems. For example, in clinical trials, participants showed enhanced immune responses, reduced inflammation and improved cardiovascular health without serious adverse effects.

This study included 218 participants aged 65 and over, divided into several groups receiving different doses of everolimus or a placebo. The results showed that the everolimus groups had significantly better immune responses, measured by higher antibody titres after vaccination.

In addition, this study revealed that the doses of everolimus administered did not induce any significant side effects, with a tolerance profile similar to that of placebo. This absence of notable side effects is crucial, as it reinforces the idea that rapamycin and its derivatives can be used without major risks in an ageing population. The results indicate that rapamycin could be used not only to improve the immune response in the elderly, but also potentially to reduce the incidence of infections in general, paving the way for important new clinical applications.

Therapeutic potential of rapamycin

Rapamycin’s therapeutic potential extends beyond simple immune rejuvenation. By reducing chronic sterile inflammation and modulating the immune response, rapamycin could improve resistance to infection and increase longevity. Studies have also suggested that rapamycin may have beneficial effects on other organ systems, such as the heart, brain and liver. For example, clinical trials have shown significant improvements in cardiac function and a reduction in damage caused by ageing, as well as increased neurogenesis and protection against neurodegenerative diseases.

Chronic sterile inflammation, a hallmark of ageing, is associated with many degenerative diseases and a general decline in health. By targeting this inflammation, rapamycin has the potential to delay the onset of these diseases and improve the quality of life of elderly individuals.

In addition, preliminary studies suggest that rapamycin may have beneficial effects on other organ systems, such as the heart, brain and liver. In the heart, for example, rapamycin has shown cardioprotective effects by improving cardiac function and reducing the damage caused by ageing. In the brain, it could promote neurogenesis and improve cognitive function, potentially reducing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Finally, in the liver, rapamycin could improve liver regeneration and protect against age-related liver disease.

These discoveries open up exciting prospects for the clinical use of rapamycin in ageing and age-related diseases. However, further research is crucial to better understand rapamycin’s mechanisms of action and to optimise treatment protocols in order to maximise therapeutic benefits while minimising potential risks. Long-term studies are essential to assess the lasting effects and safety of rapamycin and its derivatives, particularly on organ systems that have not yet been studied.

Sources

- Targeting ageing with rapamycin and its derivatives in humans: a systematic review

- The Role of Rapamycin in Healthspan Extension via the Delay of Organ Aging