The Cowpox virus, also known as cowpox, belongs to the Poxviridae family and the Orthopoxvirus genus. Less well known than the human smallpox virus, Cowpox remains a subject of interest for public health professionals and virology researchers. The disease it causes is characterised by skin ulcers, redness and severe oedema, which may contain pus. Symptoms also include fever, swollen glands and muscle pain, followed by the appearance of ulcers with a blackish centre. Fortunately, the disease usually scabs over and heals within a month on average.

What is cowpox virus?

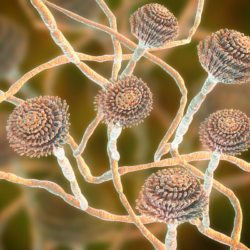

The Cowpox virus, a member of the Poxviridae family and the Orthopoxvirus genus, is responsible for the infectious disease known as cowpox. The Cowpox virus genome exceeds 220 kpb, making it the largest genome of the Orthopoxviral species. Divided into three distinct regions, comprising two terminal regions named R1 and R2 as well as a central core region, this genome features inverted terminal repeats measuring around 10 kpb, subdivided into two distinct sections.

The Cowpox virus has a rich genome, encoding 30 to 40% of the products involved in its pathogenesis, and has the most complete set of genes of all the orthopoxviruses. This unique characteristic gives it the ability to mutate into different viral strains. As a double-stranded DNA virus, it has an envelope surrounding the virion and is able to code for its own DNA transcription and replication machinery, enabling replication in the cytoplasm of the host cell.

The virus uses cellular receptors to enter the host cell, evading the immune system’s defences. It also has a wide range of cytokine responses, helping it to counter the immune system, and regulates cell signalling pathways to infect the host.

Cowpox virus displays basophilic and acidophilic inclusions in infected cells, requiring further research to fully understand their role in the viral life cycle. Finally, Cowpox virus is zoonotic and can be transmitted between different species, raising public health concerns.

What are the symptoms in animals?

Cowpox virus can infect a variety of species, mainly wild rodents, pets such as rodents and cats, and cattle. It is distributed worldwide, although the frequency of cases is not well known. In developed countries, cases of infection in cattle are rare.

The cowpox virus is transmitted mainly through contact with a contaminated animal. Cattle, voles, cats, field mice, rats and mice are potential reservoirs of the virus. In rodents and cats, transmission generally occurs through contact with an infected animal.

Symptoms of cowpox infection vary depending on the species affected. In rodents, few symptoms are visible, although mortality is possible. In cats, crusty lesions can be seen on the head and ears, as well as vesicles in the oral cavity and on the tongue. In the most severe cases, the disease can be systemic, affecting internal organs, mainly the lungs, and a fatal outcome is often associated with secondary bacterial infection.

Wild rodents, such as voles and wood mice, are considered natural reservoirs of the cowpox virus. Although cases of cowpox were reported in Europe until the early 1970s, cowpox infections are now mainly associated with domestic cats, which occasionally hunt these wild rodents. Pet rats have also been responsible for human infections.

How is this virus transmitted?

Transmission of the cowpox virus in rodents and cats occurs through direct contact with an animal carrying the virus. Rodents, such as voles and mice, can be natural hosts for the virus and transmit it through their secretions and excretions, as well as through direct physical contact. Similarly, cats can contract the virus by hunting and killing infected rodents, and transmit it through their saliva when grooming themselves or by contact with infected wounds.

In humans, transmission of the cowpox virus generally occurs through direct skin contact with an infected animal, even in the absence of an apparent bite or scratch. Transmission routes mainly involve mucous membranes and the skin. Historically, transmission to humans was mainly associated with contact with infected cows, where people who worked closely with these animals were particularly exposed. However, in recent decades, transmission to humans has occurred more frequently through contact with infected cats, although these cases remain relatively rare overall.

The areas most frequently affected by skin lesions are the hands and face, where pimples can develop and be particularly painful. Direct handling of infected animals, particularly when grooming or handling wounds, increases the risk of transmission of the virus. It is also important to note that there is no known evidence of human-to-human transmission of the cowpox virus, which means that the disease is spread mainly through contact with infected animals.

How does the disease manifest itself in humans?

Occupations at risk include all those involving close contact with rodents and cats, such as staff working in pet shops, breeders and vets. These professions are particularly exposed to transmission of the cowpox virus because of their regular interaction with animals.

The symptoms and course of cowpox infection are characterised by skin lesions that develop into a blackish crust, which may be accompanied by fever, swollen lymph nodes and muscle pain. In humans, symptoms include large blisters on the skin, fever and swollen lymph nodes. Most people are susceptible to the disease, especially children, who are more likely to be in close contact with the virus. The clinical course of the disease in humans is a painful localised skin lesion with local adenopathy and “flu-like” symptoms, which generally heals in 6 to 8 weeks. However, severe forms are possible, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, with the development of a fatal generalised infection.

Skin lesions observed at the scab stage are 1 to 2 cm in diameter, thick, adherent and may vary in colour from yellow-brown to red. Microscopic biopsies of the lesions reveal images of vacuolisation, ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes and the presence of intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies specific to Poxviridae.

How is bovine pox treated?

Treatment of cowpox relies mainly on supportive measures, as there is currently no specific antiviral treatment for CPXV. Therapeutic efforts are focused on managing symptoms and preventing complications.

In the event of infection with the cowpox virus, patients may receive treatments to relieve symptoms, such as antipyretics to reduce fever and analgesics to relieve associated muscle pain. Antibiotics may also be prescribed if a secondary bacterial infection is suspected.

At the same time, it is crucial to adopt preventive measures to limit the spread of the infection. Patients in contact with infected animals should use protective gloves to avoid direct contact with animal skin lesions, and maintain rigorous hand hygiene. Any wounds or exposure to infected material should be cleaned and disinfected immediately.

In severe cases, or in patients with risk factors such as immunodepression, hospitalisation may be necessary for close monitoring and appropriate medical treatment. However, most cases of cowpox are self-limiting and resolve spontaneously within a few weeks.

It is also important to raise awareness among healthcare professionals and the public of measures to prevent and manage cowpox infection in order to reduce the risk of spread and associated complications.

What are the means of prevention?

General prevention measures aim to reduce the spread of cowpox infection in rodents and humans. In the case of rodents, it is essential to prevent any risk of direct or indirect contact between farmed rodents and wild rodents. This can be achieved by setting up physical barriers and maintaining adequate sanitary conditions in facilities.

For humans, rigorous general hygiene is recommended. This includes controlling the presence of rats by avoiding attracting them with food deposits and by carrying out regular pest control operations. Regular cleaning and disinfection of premises, equipment and rodent cages are also crucial to preventing the spread of infection.

It is important to provide adequate training and information to employees on the risks associated with the cowpox virus, as well as on collective and individual prevention measures. This includes the correct handling and restraint of rodents and cats, as well as the provision of appropriate means such as personal protective equipment and a first aid kit.

In the event of an animal disease, the first step is to find the source of the contamination and eliminate batches of infected rodents. It is also crucial to reinforce hygiene and disinfection measures to reduce the risk of contamination by wild rodents. Compliance with hygiene rules, such as frequent hand washing and the wearing of appropriate protective equipment, is essential to prevent transmission of the infection to humans. Finally, if the animal disease is confirmed, hygiene instructions must be reinforced, such as the requirement to wear gloves when handling rodents, cages and droppings.

What is the status of this disease?

As far as animal health is concerned, the cowpox virus is not considered to be a contagious animal disease, which means that it is not widely known to spread easily between animals. However, from a public health perspective, cowpox is a notifiable disease, meaning that cases must be reported to the relevant health authorities. This classification is important to enable the disease to be properly monitored and control measures put in place if necessary.

At present, although cowpox is a public health concern, it is not listed in the table of occupational diseases. This means that it is not officially recognised as a disease that can be contracted in the course of professional activity, and therefore workers affected by this disease do not benefit from official recognition of work-related conditions.

The cowpox virus is classified in hazard group 2 under the French Labour Code (article R.4421-3). This classification indicates that the virus is considered to present a certain level of risk to human health, but does not pose a serious or immediate threat. This may involve specific prevention and control measures in the workplace to minimise workers’ exposure to the virus and reduce the risk of transmission.

Epidemiology

CPXV is widespread in Europe, Russia and the western states of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, as well as adjacent regions of North and CentralAsia. Other orthopox viruses remain present in certain communities and continue to infect humans, such as the cowpox virus in Europe and the Monkeypox virus in Central and West Africa. In Europe, the virus is mainly present in the UK. Human cases are now very rare and are most often contracted from domestic cats. The virus is rare in cattle; the reservoir hosts are wood rodents, particularly voles. Although cases of bovine pox were frequently reported in Europe until the early 1970s, they are now mainly associated with domestic cats.

Cases in the UK

A case of cowpox has been documented in the United Kingdom, according to an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine on 5 June 2021 (Kiernan M. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun 10;384(23):2241.). A 28-year-old woman presented to the emergency department of the Royal Free Hospital in London with eye irritation accompanied by redness and discharge in the right eye over a period of 5 days. The clinical situation deteriorated, leading to orbital cellulitis, which required surgery. The patient mentioned that her cat had developed lesions on the legs and head two weeks previously.

Analyses of the lesions on the cat and the woman’s eye revealed the presence of orthopoxvirus, a family of viruses including smallpox virus, vaccinia, bovine pox virus and monkeypox virus. Genetic sequencing confirmed that the patient had been infected with Cowpox virus.

This observation underlines the importance of vigilance in the face of zoonotic diseases, i.e. those that can be transmitted from animals to humans. It also highlights the potential role of pets, such as cats, in the transmission of certain viruses, and underlines the importance of collaboration between human and animal health professionals to monitor and control such diseases.

Situation in France

A study conducted between 2008 and 2009 revealed a series of cases of ulceronecrotic skin lesions, first reported on 16 January 2009 by an infectiologist at Compiègne Hospital. Three patients presented with these symptoms between 4 and 14 January 2009, with no improvement after initial treatment and antibiotics. Biological and bacterial investigations were unsuccessful, but the patients had all purchased pet rats from the same pet shop between 22 December and 3 January.

After an inspection of the pet shop by the DDSV 60, the hypothesis of a viral infection, in particular cowpox, was put forward. Further evidence gathered between 19 and 23 January confirmed this hypothesis, with a resurgence of human cases of cowpox skin infections in Germany. Biopsy samples taken on 26 January revealed viral morphologies compatible with cowpox in two patients.

The multidisciplinary investigation carried out by the InVS, the DGAL and other bodies defined confirmed and probable cases of cowpox infection, with an in-depth analysis of the epidemiological and clinical characteristics. A total of 20 cases were identified, with a predominance of females and characteristic skin lesions progressing to necrosis.

Control measures were quickly put in place, including the withdrawal of potentially contaminated rats from pet shops and information campaigns aimed at health professionals and the general public. This study highlights the importance of collaboration between local and national health authorities to ensure an effective response to such epidemiological situations.

Cowpox and smallpox vaccine

The discovery of cowpox dates back to 1798 thanks to Jenner, who introduced the term “vaccination” derived from the Latin adjective “vaccinus”, meaning “of the cow”. Patients develop immunity to both bovine and human smallpox after vaccination, which eventually led to the eradication of smallpox in 1980 according to the WHO.

The origins of vaccinia date back to the years 1770-1790, with farmers and livestock workers often spared during smallpox epidemics. Initially, vaccination involved the use of lymph from the pustules of smallpox-infected cows, but complications led to the introduction of safer methods, such as “retrovaccination” in Italy.

This method involved inoculating cows with the humanised bovine smallpox virus, then transmitting it from one heifer to another to produce vaccine in massive quantities. Subsequently, the “real animal vaccine” was developed, using naturally occurring animal smallpox virus.

Vaccine production became lucrative, with many entrepreneurs producing crude versions from calves and infected cow lymph. Early uses of the vaccine involved the transfer of human fluids, but a mutation led to the use of ‘vaccinia’ rather than smallpox.

Jenner conducted experiments in 1796 confirming this theory, thus popularising vaccination. The cowpox virus made it possible to prevent smallpox, save lives and reduce the costs associated with the disease. Despite concerns about transmission and the potential complications of vaccinia, it was widely accepted as the main method of preventing smallpox until it was eradicated in 1980.