Brucellosis, a bacterial zoonosis of global importance, is attracting increasing interest due to its impact on public health, animal health and the economy. The disease is caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella. It can be transmitted directly or indirectly between animals and humans. This infection particularly affects domestic and wild ruminants, as well as swine. As well as causing major economic losses for livestock farmers, brucellosis can lead to severe complications in humans. Symptoms can range from intermittent fevers to serious osteoarticular complications in chronic cases.

What is the infectious agent?

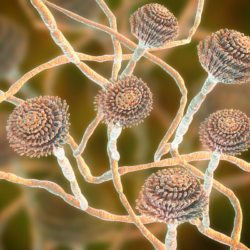

Brucellosis is a zoonosis caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella. It is a worldwide disease that can affect both humans and most mammalian species, particularly domestic and wild ruminants, as well as swine such as pigs and wild boar. Brucella spp are gram-negative bacteria, very small in size (0.5-0.7 x 0.6-1.5 µm), immobile, non-encapsulated, non-spore-forming, strict aerobes and facultatively intracellular.

Several Brucella species are pathogenic to humans, notably B. melitensis, B. abortus bovis, B. suis and, secondarily, B. canis.

Brucella are capable of surviving for long periods in the outdoor environment, with their lifespan varying according to the conditions. They can live for up to 32 days in dry, non-organic environments, more than 125 days in moist organic environments and up to 135 days in dry organic environments. In blood stored at 4°C, they can survive for up to 180 days.

Domestic ruminants, particularly sheep and goats, are the main reservoir of human brucellosis. Cattle are mainly infected by Brucella abortus, while pigs are affected by Brucella suis.

Brucellosis is classified as a level 3 biohazard in France. It is considered a potential agent of bioterrorism in the United States. Its pathogenic mechanism remains poorly understood. However, it is known to involve dissemination into lymph nodes and organs of the reticuloendothelial system. What’s more, this bacterium can evade the immune system by developing inside phagocytic cells. In animals, Brucella has a particular tropism for the placenta. This can lead to serious complications, including foetal death.

How does the disease manifest itself in animals?

Brucellosis, a bacterial zoonosis of global importance, affects a wide range of mammalian species. Bacteria of the Brucella genus, notably B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. suis and B. canis, mainly target cattle, small ruminants, pigs, wild boar, hares and dogs. The manifestations of the disease vary depending on the species. They generally include abortions, reproductive disorders and joint lesions.

In animals, brucellosis is often asymptomatic but can lead to abortions. Brucellosis pathogens have a particular affinity for the genital organs. This facilitates their transmission through milk or sexual contact. In cattle, for example, brucellosis can persist for years in the lymph nodes without triggering any immediate symptoms. On the other hand, it can lead to late abortions in pregnant females.

The disease confers partial immunity, although some individuals may continue to abort or produce inferior offspring. Transmission is mainly sexual in pigs and small ruminants. In dogs, it can cause fever, late abortions and testicular lesions in males.

In domestic animals, brucellosis can cause significant economic losses due to reduced fertility and abortions. Prevention of the disease involves strict biosecurity measures. These include screening and vaccination programmes, particularly in breeding herds. A thorough understanding of theepidemiology and clinical manifestations of brucellosis is essential to implement effective control and management strategies for this infectious disease.

How is brucellosis transmitted?

Adult animals with brucellosis can excrete the bacteria throughout their lives in milk,urine and genital secretions. This excretion is greatest at the time ofabortion or parturition. Transmission from mother to foetus or newborn is possible. Contamination of the environment (breeding premises, pastures, etc.) and the keeping of young females born to infected dams (5 to 10% harbour brucella) are at the root of a resurgence of the disease in herds that have been cleaned up.

Brucellosis is generally spread at the time of reproduction,abortion or parturition. High concentrations of bacteria are found in abortion products and foetal water from an infected animal. The bacteria can survive for several months outside the animal’s body. They survive mainly in the outdoor environment, particularly in cold, damp conditions. These bacteria in the environment remain a source of infection for other animals that become infected through close contact(respiratory or conjunctivalroute, or even ingestion). The bacteria can also colonise the udder and contaminate the milk.

Human infection occurs in different ways. Most often, transmission to humans occurs through ingestion of fresh dairy products (raw milk) from animals infected with the bacteria. It can also occur through contact with animals infected with brucellosis. This is particularly the case for livestock farmers, vets and abattoir staff exposed to infection by handling infected animals, runts and placentas. People can also be infected by handling manure or other contaminated products, ingesting vegetables from soil treated with manure, orinhaling dust from contaminated bedding.

What are the symptoms in humans?

The symptoms and course of brucellosis vary according to the form of infection and the stage of the disease. The most common forms, mainly with B. abortus, present as minor flu-like symptoms. Three forms are observed:

- The acute septicaemic form (or Malta fever) is characterised by undulating fever, particularly at night, with sweating and pain, lasting about 15 days after an incubation period of 8 to 21 days.

- The subacute or localised form can affect any organ, such as the testicles, heart, lungs, joints, etc.

- The chronic form, without fever, is characterised by extreme fatigue and osteoarticular pain.

In pregnant women, acute brucellosis can lead to abortion or premature delivery. Primary infection may be asymptomatic or manifest itself with mild symptoms and go unnoticed. Subsequently, the infection may remain silent for several months or even years before reactivating. In humans, the disease presents non-specific signs ranging from isolated fever or a common flu-like syndrome to localised infections such as arthritis, orchitis or meningitis.

Complications of brucellosis are rare but may include subacute bacterial endocarditis, neurobrucellosis (meningitis, encephalitis, neuritis), orchitis, cholecystitis, liver suppurations and osteomyelitis. The disease can progress to a chronic form. The latter is characterised by persistent asthenia and slowly progressive suppurative foci. This places a heavy burden on the patient in terms of health and quality of life.

Some epidemiological data

Brucellosis is a worldwide disease, but its prevalence varies from region to region. In France, the frequency of cases is generally low, with only 25 cases diagnosed in 2003 in mainland France and 2 in New Caledonia. Most cases are linked to infection abroad, particularly in Mediterranean countries, where the disease is more widespread. Travellers can become infected by consuming contaminated local cheeses or dairy products.

The brucellosis situation in France has evolved over time. Since 2005, France has been officially declared free of bovine brucellosis under European regulations. However, a number of outbreaks of bovine brucellosis were identified in 2012, underlining the need for ongoing vigilance. In addition, brucella infection in swine, particularly pigs and wild boar, reappeared in 1993. This has led to the discovery of numerous outbreaks since then.

Most cases of human brucellosis in France are imported. They occur in people who have travelled to countries where the animal disease is present and poorly controlled. In 2017, most of the 32 cases reported were imported, mainly fromAlgeria, Tunisia and Lebanon. Indigenous cases have become rare. There have been fewer than 1 case per million people per year since the 2000s.

Brucellosis remains a major public health concern. It requires ongoing surveillance and effective control measures to prevent its spread, particularly in areas where it is endemic.

What are the repercussions of this zoonosis?

Occupational activities at risk of contracting brucellosis include working directly with infected animals or their contaminated environment. This applies in particular to livestock farmers, vets, slaughterhouse workers and veterinary laboratory staff. The latter are exposed during births, abortions and the handling of carcasses. Because of its economic impact and threat to health, national and international health authorities are keeping a close eye on brucellosis. The Anses animal health laboratory in Maisons-Alfort is a reference in this field. It provides expertise and technical advice to Member States, with the support of the WHO, for the management of brucellosis in humans and animals.

ANSES actions

The ANSES animal health laboratory in Maisons-Alfort is a national, European, WHO and FAO reference centre for animal brucellosis . It is also a national reference centre for human brucellosis. It plays a key role in the surveillance of animals and human cases in France. The centre coordinates the activities of a network of national and European laboratories. It also contributes to the development of prevention, surveillance and eradication strategies . It therefore works closely with national and international health bodies.

The research carried out at the Anses aims to improve diagnostic tools for infection in animals and humans, as well as epidemiological knowledge of brucellosis in all susceptible species, both domestic and wild.

Since 2013, following the detection of brucellosis in certain individuals, the Anses has drawn up several expert reports on ibex populations in the Bargy massif. The aim is to limit the risk of contamination of domestic animals and to encourage thenatural extinction of the disease in the wild population.

The strategy recommended by the Agency is based on a combination of capture and targeted shooting of the animals most at risk of becoming infected and transmitting the disease. This approach makes it possible to :

- monitor the level of infection in ibex,

- combat infection by euthanising infected animals,

- mark animals not carrying the pathogen before releasing them.

This strategy is considered preferable to a mass slaughter of ibex. This would eliminate a large number of healthy individuals. In addition, this method would make it difficult to monitor and detect any resurgence or spread of the infection to other areas.

WHO actions

TheWHO plays a crucial role in the fight against brucellosis. It provides technical advice. It also develops standards and guidelines for its management. This advice is intended to help Member States put in place effective measures to prevent, monitor and treat the disease.

One of the WHO’s priorities is to promote coordination between the public health and animal health sectors. This collaboration is essential for an integrated and coherent response to brucellosis. It takes into account the interactions between human, animal and environmental health.

In partnership with other organisations such as the FAO, theOIE and the Mediterranean Zoonoses Control Programme, the WHO is building the capacity of countries to prevent and manage brucellosis. This collaboration takes the form of the global early warning and response system for animal diseases. This system enables rapid sharing of information and concerted action to control the spread of the disease.

Disease status

How can this disease be diagnosed?

Brucellosis generally presents with flu-like symptoms, including fever, asthenia, malaise and weight loss. However, it can also take a variety of atypical forms, which sometimes makes it difficult to diagnose. The incubation period varies from 1 week to 2 months, but is generally 2 to 4 weeks.

Diagnosis of brucellosis is based on several methods, including blood cultures, bone marrow and cerebrospinal fluid cultures, and acute and convalescent phase serological tests. Detecting the presence of the bacteria requires blood cultures, but these can take more than 7 days to grow, and the samples must be able to be stored for several weeks. Serological tests can also be carried out. However, they are not reliable for all Brucella species, particularly B. canis.

Positive diagnosis involves specific biological and bacteriological examinations, as well as serological tests. Infectious outbreaks can be detected by taking samples from affected areas. Molecular diagnosis by PCR can also be used to detect the presence of the pathogen.

The differential diagnosis of brucellosis must be made on the basis of symptoms and test results, to exclude other diseases such as Q fever, yersiniosis, or viral infections such as primary cytomegalovirus infection or typhoid fever.

What treatment is available in the event of contamination?

The treatment of brucellosis requires a multifaceted approach. As well as administering specific antibiotics for several weeks, it is advisable to limit activity during the acute phases, with bed rest during febrile episodes. Severe musculoskeletal pain may require analgesics. Brucella endocarditis may require surgery in addition to antibiotic treatment.

Antibiotics should be administered in combination to reduce the risk of recurrence, with specific protocols depending on the severity and presentation of the disease. Clinical monitoring and serology titers are recommended for at least one year after treatment, as approximately 5-15% of patients may relapse.

Antibiotic treatment should be initiated promptly to avoid chronic infection. Tetracyclines are generally used in combination with aminoglycosides. For severe forms, the WHO recommends dual therapy with rifampicin and doxycycline. Antibiotic susceptibility testing is not necessary due to the high sensitivity of Brucella strains to the recommended antibiotics.

The duration of treatment varies according to the stage of the disease, but may be prolonged in cases of chronic brucellosis. Symptomatic treatment may be necessary to relieve asthenia and pain. Early antibiotic treatment can reduce the duration of the acute phase and prevent visceral and osteoarticular complications.

How can infection be prevented?

General prevention measures include rigoroushygiene practices on farms. These include

- regular cleaning and disinfection of premises and equipment,

- appropriate storage of waste and animal carcasses.

- regular serological screening

- the introduction of new animals only fromfree farms.

Vaccination of animals is prohibited in France because it interferes with serological screening tests, except under certain specific conditions.

Staff must be made aware of the risks associated with brucellosis and trained in preventive measures. They must be provided with adequate personal protective equipment and appropriate means ofhygiene.

In the event of proveninfection, strict control measures are necessary, including :

- surveillance of livestock

- isolation of sick animals

- disinfection of contaminated facilities and effluents,

- and possibly theslaughter of infected animals.

To reduce sources of contamination, it is advisable to avoid using high-pressure water jets when cleaning animal droppings. Protective equipment should also be worn when handling animals, cadavers or waste. Compliance with personalhygiene rules, such as regular hand-washing and wearingprotective equipment, is also essential to prevent transmission of the disease.

Finally, pasteurisation of milk is a crucial measure for preventing brucellosis in humans. It is recommended that pasteurised milk products be consumed. There is currently no commercially available vaccine for humans. Epidemiological vigilance, as well as compliance withhygiene and biosecurity standards, remain essential to controlling the spread of the disease.