Fungal zoonoses are a growing threat to human health, with major implications for public health and veterinary medicine. Among these emerging pathologies, aspergillosis is of particular concern due to its virulence and transmissibility between animals and humans.

What does the disease look like in animals?

The epidemiology of aspergillosis reveals a significant prevalence in various animal species. Particular attention is paid to intensively farmed birds, such as turkeys, and to parrots and parakeets in aviaries. Mammals, including dogs, horses and ruminants, are also susceptible to Aspergillus infection. The geographical distribution of cases of aspergillosis is worldwide, favoured by a hot, humid climate followed by a dry period.

The pathogen is mainly transmitted by air, from contaminated environments such as hay, grain or animal feed. The clinical manifestations of the infection differ according to the animal species concerned. In birds, respiratory symptoms predominate, while in dogs, epistaxis is frequently observed. In horses, signs mainly include acute difficulty in ingesting food. Although less common in mammals,aspergillosis remains a concern, particularly in immunocompromised animals. In birds, it is a major cause of mortality.

Rhinosinus aspergillosis in dogs

Rhinosinus aspergillosis in dogs affects the nasal cavities and/or sinuses, mainly the frontal sinuses. It accounts for 12% to 34% of cases of chronic rhino-sinus disease in dogs. It mainly affects young, active, dolichocephalic dogs. Tumours, bacterial infections, foreign bodies and nasal-sinus trauma are aggravating factors. Symptoms include:

- snoring

- epistaxis

- mucopurulent discharge

- ulceration of the nostrils

- a sometimes hyperkeratotic nose

- and satellite adenitis.

If left untreated, an invasive form may develop. This leads to bone lysis, facial deformity, uveitis, panophthalmitis and brain damage, sometimes with a fatal outcome.

In addition to this rhino-sinusal form, dogs can also develop pulmonary aspergillosis, which is rarer in felines. Cases of disseminated aspergillosis with paralysis and spinal pain have been reported in German Shepherds, although these have not yet been documented in France.

Diagnosis of rhino-sinusal aspergillosis is based on :

- clinical and epidemiological signs

- serological, histological

- histological

- cytological analyses

- and mycological cultures,

- as well as medical imaging.

The preferred treatment is balneation of the nasal cavities and frontal sinuses with an azole derivative. This may be supplemented by systemic antifungal treatment in the event of invasion.

Aspergillosis of the guttural pouch in horses

Guttural pouch aspergillosis in horses, mainly caused by A. nidulans and A. fumigatus, is transmitted by oropharyngeal contamination during exhalation and swallowing. Symptoms include snoring, mucopurulent discharge, unilateral and intermittent epistaxis and pain on parotid palpation. Arterial, venous and neurological complications can occur, causing haemorrhage and disorders such as dysphagia and laryngeal paralysis. Although rare, horses can also develop pulmonary aspergillosis.

Environmental conditions that favour conidial germination and tissue trauma are predisposing factors. Diagnosis is based on histological and cytological examinations, mycological cultures and medical imaging tests such as endoscopy and radiology. Angiography can be useful in locating damaged arteries.

Treatment of aspergillosis of the guttural pouch is mainly surgical. Ligation of the arteries weakened by the fungal plaque is essential to stop and prevent serious haemorrhage. This procedure allows rapid, spontaneous healing of the fungal lesions within a few weeks. Ligation of the common carotid artery can be carried out as an emergency measure to control haemorrhage or on animals of low economic value. If the medial compartment is affected, ligation of the internal carotid artery is necessary.

Abortion in cattle

Aspergillosis in cattle leads to sporadic abortions during the second or last third of gestation. This condition does not affect the fertility of the cow and does not systematically affect the foetus. Cases of aspergillosis in cattle are mainly seen in winter, when the animals are confined to their buildings and the silage is contaminated. Contamination occurs mainly through ingestion. In addition to abortions, cases of pulmonary aspergillosis, aspergillosis mastitis and disseminated forms of the disease, particularly in calves, have also been described.

Aspergillosis in birds

Aspergillosis in birds, also known as pulmonary aspergillosis, bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or aspergillary pneumomycosis, is characterised by airborne contamination, with the deep respiratory tract the preferred site for development of the fungus. Avian aspergillosis is mainly caused by A. fumigatus, followed by A. flavus. Clinical symptoms are often non-specific, such as lethargy,inappetence or anorexia, or may be directly related to respiratory involvement, including dyspnoea, rhinitis or voice changes. The lungs and air sacs are mainly affected. Diagnosis is based on haematological, cytological and histological analyses, mycological cultures and medical imaging examinations such as radiology and tomography.

How is it transmitted?

Aspergillus is transmitted mainly by inhalation of airborne spores. This occurs when mould-contaminated dust is suspended in the air, particularly when handling compost, hay or grain. Contrary to widespread belief, contamination does not come from an animal suffering from aspergillosis, as the disease is not contagious. However, several routes of contamination are possible, including the respiratory, digestive, cutaneous, transplacental and transcoquillial routes. The respiratory route is the most common, with inhaled conidia penetrating deep into the respiratory tract. Birds, cattle and horses can be contaminated by inhalation of conidia released from contaminated bedding or feed.

Environmental conditions, such as heat and humidity, favour Aspergillus sporulation. This increases the likelihood of air contamination. Animals raised on plant substrates and fed on forage and silage are more susceptible to contamination. This vulnerability is also evident in individuals exposed to poor zootechnical methods. In addition, anatomical characteristics specific to certain species and breeds, as well as the presence of pre-existing pathologies, trauma or foreign bodies can increase the risk of developing aspergillosis.

The disease develops more easily in individuals who are immunocompromised, stressed or exposed to prolonged therapies such as antibiotics or corticosteroids. It can affect various domestic species and captive wild animals, with clinical forms and locations varying according to the host.

What are the symptoms in humans?

In humans, aspergillosis mainly affects immunocompromised individuals, becoming an opportunistic infection. The causes of this immunosuppression are diverse: HIV infection, aplasia due to chemotherapy or acute leukaemia, immunosuppressive treatment following organ transplants, or even congenital immune deficiencies. Neutropenia is the main risk factor for serious invasive infection. The main risk factors for aspergillosis are :

- Prolonged neutropenia (typically > 7 days)

- Long-term, high-dose corticosteroid therapy

- Organ transplants, particularly bone marrow transplants with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

- Inherited disorders of neutrophil function, such as chronic granulomatosis

A. fumigatus is the most common cause of invasive lung infections. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is a hypersensitivity reaction to A. fumigatus, triggering pulmonary inflammation independent of the fungal infection. Focal infections are generally located in the lungs, sometimes forming aspergillomas, masses of filaments embedded in a protein matrix, observed particularly in patients with pre-existing lung cavities. Pulmonary invasive aspergillosis is the most serious form, affecting mainly immunocompromised patients, and is a major cause of death in leukaemia and organ transplant units.

Clinical presentation

There are two forms of aspergillosis: invasive and non-invasive. The invasive form, which is more severe, involves invasion of the lung parenchyma by the fungus, which can then spread to other organs, leading to a risk of arterial damage, ischaemia, necrosis and destruction of the lung parenchyma.

A study carried out in 2000 by the Agence nationale d’accréditation et d’évaluation en santé (ANAES) and the Société française d’hygiène hospitalière (SFHH) identified two main risk factors for invasive aspergillosis in hospitals: host immunodeficiency and exogenous environmental factors. Among the latter, work carried out on the hospital site leads to a significant increase in risk. Major building works and minor maintenance work multiply airborne concentrations of Aspergillus fumigatus, flavus and niger spores.

The clinical spectrum of aspergillosis is broad, varying in severity and in the site affected. Clinical signs depend on the type of infection and its location, but the lung is mainly affected.

Pulmonary aspergillosis is divided into three types: invasive, aspergilloma and allergic bronchopulmonary. Severe invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurs mainly in neutropenic immunocompromised patients and can lead to septicaemia. Conversely, aspergilloma is a local infection in a lung cavity colonised by Aspergillus. Finally, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis results from an allergic reaction to Aspergillus and presents symptoms similar to asthma.

Aspergillosis can also affect the skin, manifesting as nodules, erythematous plaques or maculopapules, and the sinuses, with aspergillosis sinusitis. It can also affect the brain, causing meningitis or encephalitis, especially in immunocompromised patients or after local contamination.

Invasive forms

Invasive aspergillosis is a serious infectious disease caused by the widespread dissemination of a fungus of the genus Aspergillus, principally Aspergillus fumigatus. It mainly affects immunocompromised patients, and is the second most common cause of hospital death due to fungal infection. Pulmonary involvement is the most common. It occurs mainly in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with neutropenia. Approximately 5-25% of patients with acute leukaemia, 5-10% of bone marrow transplant recipients and 0.5-5% of patients undergoing anti-rejection treatment after organ transplantation are affected. The risk of invasive aspergillosis varies between organ transplants, with a higher prevalence in heart-lung transplants, followed by liver, heart, lung and kidney transplants. In addition, HIV patients are also increasingly affected by this disease.

The clinical manifestations of invasive aspergillosis depend on the infected organ and the underlying condition. Four main types are distinguished: acute or chronic invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, tracheobronchitis and obstructive bronchitis, acute invasive rhinosinusitis, and finally diffuse invasive aspergillosis, involving several organs such as the brain and skin. Complications can also arise in the kidneys, heart, bone marrow and eyes, although less frequently. Fever is not always present, especially in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Invasive aspergillosis is the second most common cause of hospital death due to fungal infection.

Non-invasive forms

Non-invasive forms of aspergillosis are characterised by localised proliferation of the fungus with no diffuse spread throughout the body. The most common forms are aspergilloma and aspergillosis sinusitis, the latter of which may develop into an invasive form.

Aspergilloma, or chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, results from colonisation of a lung cavity by a fungus of the genus Aspergillus. It often occurs as a complication of tuberculous caverns, a common sequelae of pulmonary tuberculosis, leading to local destruction of the lung. Every year, around 370,000 people develop an aspergilloma, with different forms depending on the size and degree of associated lung destruction. Bleeding, leading to expectoration of blood, is a major complication of aspergilloma, sometimes life-threatening.

In terms of pathophysiology, the formation of tuberculous caverns results from the destruction of lung parenchyma following the initial tuberculosis infection. Pathogenesis probably involves a phase of initial adhesion ofAspergillus spores to the respiratory epithelium. This adhesion is followed by the secretion of proteolytic enzymes that facilitate fungal colonisation and provoke a local inflammatory reaction.

Clinically, aspergilloma often presents with haemoptysis and a productive cough. However, it can also present with less specific symptoms. The prognosis for this condition is worrying, with an estimated annual mortality rate of between 5 and 6%. This rate can rise to 26% in cases of massive haemoptysis.

Aspergillosis generally manifests itself as a chronic infection of the sinuses, sometimes in a pseudotumourous form. Diagnosis is based on medical imaging and sometimes bacteriological and mycological tests. Clinical forms vary from chronic invasive to non-invasive, with symptoms including nasal obstruction, pain, rhinorrhoea and nasal polyps. In severe cases, complications may arise, including ocular abscesses or endocranial complications, sometimes threatening the prognosis.

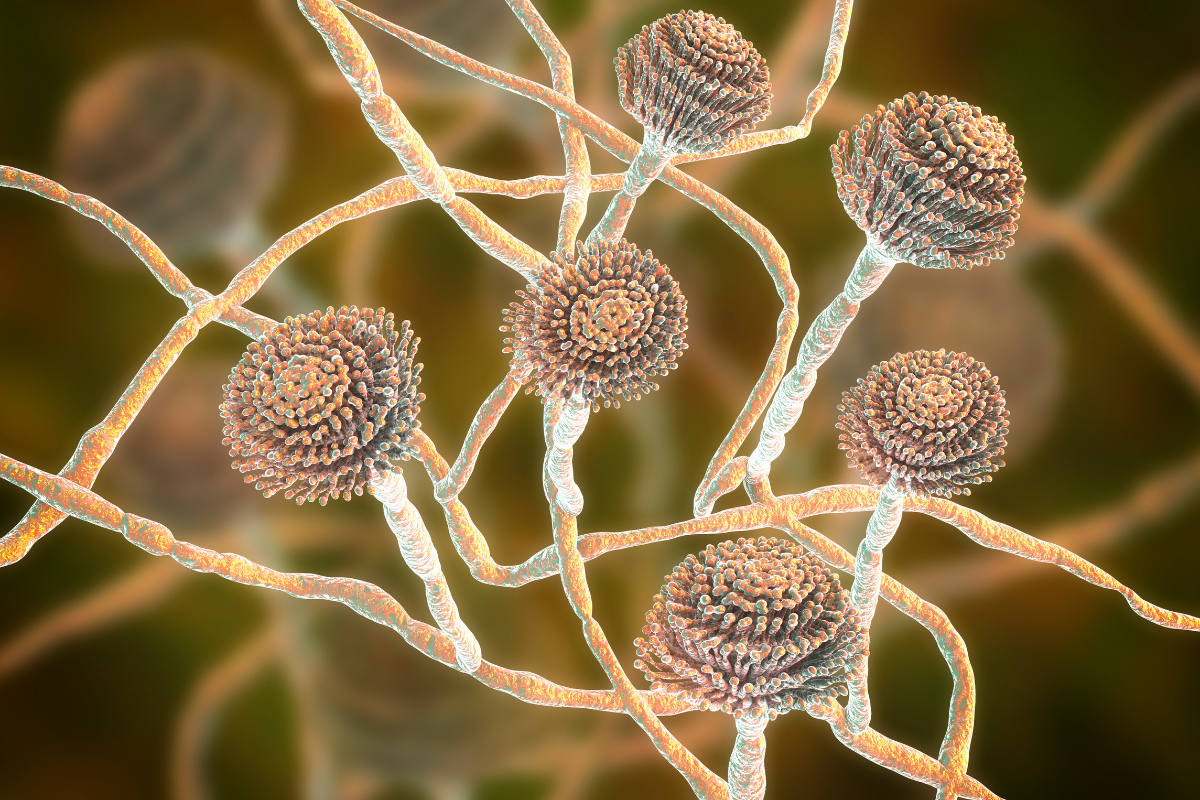

Zoom on Aspergillus

Species of the Aspergillus genus are saprophytic fungi, widely distributed in the environment and regularly inhaled by the human population. They colonise natural cavities exposed to dust, mainly the respiratory tract such as the bronchi and lungs, and sometimes the external auditory canals, without causing significant damage.

However, these fungi can become pathogenic and cause specific conditions known as aspergillosis, especially in immunocompromised individuals. The species responsible include Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus versicolor, Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus terreus. Of these, Aspergillus fumigatus is of particular concern, being an opportunistic agent that can cause illness in people with weakened immune systems.

Aspergillus, which belong to the Fungi kingdom, are eukaryotic organisms with a syncytial structure and are characterised by their heterotrophic mode of nutrition. They reproduce sexually or asexually. Traditionally, they are classified in the Ascomycota. Although asexual reproduction predominates, some members of this genus are also capable of sexual reproduction.

In terms of pathogenicity, various factors influence Aspergillus infections, including the virulence of strains, environmental exposure and host susceptibility. Aspergillus are capable of synthesising various mycotoxins, such as gliotoxin and aflatoxins, which can be immunosuppressive, cytotoxic and even carcinogenic. In addition, these fungi produce antigenic molecules, such as galactomannan, used in the serological diagnosis of aspergillosis.

Aspergillosis is a mycosis that occurs worldwide, and is more common in warm, humid regions. Although it is not contagious, several routes of contamination are possible, including respiratory, digestive, cutaneous, transplacental and transcoquillial.

How is the disease diagnosed?

Diagnostic methods for Aspergillus infections generally involve culturing samples on specific fungal media and histopathological analysis of tissue samples. Testing for galactomannan antigen in serum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is also common.

Positive sputum cultures for Aspergillus may result from environmental contamination or non-invasive colonisation in patients with chronic lung disease. However, their significance is limited except in high-risk patients. On the other hand, sputum cultures are often negative in patients with aspergilloma or invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Chest X-rays are often taken. However, chest computed tomography ( CT) is more sensitive and is recommended for high-risk patients, such as those with neutropenia. A CT scan of the sinuses may be performed if a sinus infection is suspected.

Definitive diagnosis is often based on culture and histopathology of tissue samples, usually obtained by bronchoscopy or percutaneous biopsy. However, these tests can be lengthy and not always conclusive. Treatment decisions are therefore often based on a strong clinical presumption. Blood cultures are generally negative, even in cases of Aspergillus endocarditis, although echocardiograms may show signs of intracardiac vegetation.

Galactomannan antigen tests are specific but sometimes not very sensitive, particularly in early cases of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. PCR may be more sensitive than culture alone in identifying the strain of Aspergillus. In addition, galactomannan and 1,3-β-D-glucan may be elevated in blood and cerebrospinal fluid in patients with brain involvement. In the event of diagnostic doubt, the negativity of these tests may help to exclude an aspergilloma.

What is the treatment?

Treatment of aspergillosis is based on recommendations issued by the Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2008. It comprises several options, including voriconazole administered intravenously initially and then orally as soon as possible, as well as lipid derivatives of amphotericin B if voriconazole fails or is contraindicated. Caspofungin and posaconazole may be considered as second-line treatments.

Research into aspergillosis is aimed at improving our understanding of the mechanisms of infection and developing more effective treatments. Advances in microscopy and biotechnology are paving the way for new therapeutic approaches. Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic methods are being used to gain a better understanding of these pathogenic fungi. Some research institutes, such as the Hans-Knöll Institute in Jena, Germany, are focusing on this issue, exploring more effective drugs and immune enhancement techniques.

A number of drugs are used to treat aspergillosis, including voriconazole, posaconazole,isavuconazonium, amphotericin B (including lipid formulations) and echinocandins where necessary. Invasive infections are generally treated aggressively, with particular attention paid to stopping immunosuppression. Aspergillomas, on the other hand, may require surgery rather than systemic antifungal treatment, especially if there is a risk of haemoptysis.

For prophylaxis, posaconazole or itraconazole may be considered in high-risk patients, such as those with graft-versus-host disease or neutropenia associated with acute myeloid leukaemia.

Antifungal resistance

Antifungal resistance in Aspergillus is a growing challenge in the treatment of fungal infections. It is recommended that strains be tested for antifungal susceptibility once identified in culture. Different isolates from the same patient may have different susceptibilities. Since the late 1990s, resistance to antifungal agents has been emerging, with increasing prevalence, particularly in certain regions of Western Europe and Scandinavia.

Resistance is mainly associated with triazoles, a class of antifungal agents widely prescribed as first-line treatment. It is often due to mutations in the protein targeted by triazoles, lanosterol 14α-demethylase, encoded by the cyp51A gene. These mutations make strains resistant to several triazoles simultaneously. Since 2010, other resistance mechanisms have also been identified.

This phenomenon is worrying because it limits the available therapeutic options. What’s more, triazoles are often the only molecules that can be administered orally. Resistance can develop even in patients who have never received antifungals. This suggests that resistant strains are spread in the environment. Given the small number of antifungal agents available and the risk of resistance spreading worldwide, surveillance and research into new therapeutic strategies are essential to meet this growing challenge in the treatment of aspergillosis infections.

Preventing contamination

General prevention measures aim to reduce exposure to Aspergillus in the working environment, particularly in the agricultural and agri-food industries. It is essential to follow good harvesting and storage practices for animal feed, straw and bedding. Care must be taken to eliminate all potential sources of contamination. Minimising exposure to dust is essential. When using mechanised methods, good aeration and ventilation of the premises is essential, as is regular cleaning.

Making workers aware of the risks associated with Aspergillus and the importance of preventive measures is crucial. They must have the necessary means to maintain good personal hygiene. These include access to drinking water, soap, paper towels and a first-aid kit. Separate lockers prevent contamination of personal belongings. Appropriate and well-maintained work clothing and personal protective equipment are also necessary to limit exposure.

In terms of personal practices, it is recommended to maintain a distance from dust-generating operations wherever possible and to wear a FFP2 protective mask when handling mouldy materials. Personal hygiene rules, such as regular hand-washing during the working day and a ban on drinking, eating or smoking in the workplace, must be observed. It is also advisable to clean work clothes regularly and to change clothes at the end of the day.

For immunocompromised workers, it is important to follow medical advice on continuing to work. Any activity involving the dispersion of plant dust should be avoided. If you continue to work, you may need to use a respirator with assisted ventilation.

What is the status of the disease?

With regard to the status of the disease, it is important to specify that as far as animal health is concerned. Aspergillosis is not considered to be a contagious animal disease. This means that it is not generally transmissible between animals, either by direct contact or by other means of transmission.

In public health terms, aspergillosis is not notifiable. As a result, cases of aspergillosis are not systematically reported to the health authorities. Other infectious diseases require notification in order to ensure epidemiological surveillance and protect public health. It should also be pointed out that aspergillosis is not yet recognised as an occupational disease.

In other words, workers cannot benefit from the recognition of aspergillosis as an occupational disease for specific indemnities or benefits linked to their professional activity.

Finally, the classification of Aspergillus fumigatus in hazard group 2 indicates that it presents a health risk. This risk does not reach the level of danger posed by pathogens in hazard group 3. This classification is of vital importance in the field of occupational health and safety regulations. Specific measures must be put in place to prevent worker exposure to this type of pathogen.